How Many Careers Do Workers Have?

Measuring career continuity across job transitions in the NLSY79 cohort

This post is the first in a series drawing from my article with Arne Kalleberg and Ted Mouw (UNC-Chapel Hill) published in the peer-reviewed journal Social Science Research in 2025. Read the whole article.

Careers are a central concept in a sociological approach to economic mobility. A common entry-point for sociologist is to ask people about their lives, what’s happened to them, and their experiences. If you talk to people about their work lives, the notion of a career arises. People change jobs. Those job transitions can be within the same employer or across employers. They can be in the same or a different occupation as coded by an occupational classification system.

The idea of a career is that across these different job transitions there is some degree of orderliness or continuity. Gunz and Mayrhofer (2011: 254) use a definition of career that I find insightful. They describe a career as "a pattern in condition over time within a bounded social space." What they mean is that there is some boundary that links each successive state of the career to the previous state.

Now what that boundary is and how to measure it is open to debate. I think in the process of applying for a job by tailoring a resume and writing a cover letter, job seekers are making the pitch to the employer that their previous work experience is relevant to the new position; or, in other words, that the boundary of their career encompasses this new job. Whether employers see it that way is a different question, but I would contend people have experience navigating the definitional space around what constitutes the boundary of their career.

In the analysis that follows, we aren’t using data asking people to parcel their job history into careers. However, we do seek to make sense of these people work histories captured annually in real-time in a way that feels true to the notion of a career.

The NLSY79: A Remarkable Longitudinal Source of Work Histories

For our analysis, we use work history data from a nationally-representative longitudinal survey called the National Longitudinal Study of Youth (NLSY) 1979 cohort. A birth cohort are the people born in the same year. In the context of the NLSY79, the people in the survey were born between 1957 and 1964 (late Baby Boomers, including my parents) and were 14-22 when first interviewed in 1979 (hence the name). In our analysis, we follow people who remain in the survey through 2019 when the respondents were aged 55 to 62. So, we have near compete work histories as many people retire by age 62 when they become eligible for Social Security retirement benefits.

The sample consists of 12,161 people and we have a total of 276,979 observations in their work history. The crown jewel of the NLSY is that the work history information that comes in a weekly array. This means respondents are asked at each interview about each week in the previous year. Respondents report whether they are employed and their main job characteristics, including the employer, wages, and job title/description which is coded into an occupation in the occupational classification system.

It is worth pausing for a moment (particularly at this moment when social science research funding from the federal government is being questioned) on the remarkable nature of this data. The NLSY 79 cohort of respondents has been interviewed every year (biannually after 1997) for more than 40 years. We probably know more about these people’s lives than almost any other. The survey asks about a wide range of life experiences well beyond the work histories we use in our analysis. The only comparable other dataset is the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) which is similar accept it has all ages (not a cohort design).

There are now other possible longitudinal datasets including data from government administrative records, like public education records and the unemployment insurance system, and from the internet, like resume data. However, the main advantage of these government surveys is they are random samples (selected through an effort intensive process using physical addresses and follow-up) – shout out to my former colleagues at NORC at the University of Chicago who manage the data collection for the NLSY79. If you know something of statistics, a random sample means that even with a small sample we can confidently make claims about the whole population.

Finally, there is no substitute for asking people about their lives. People fill out administrative forms for many reasons and we can creatively use that data for other purposes, but that is no substitute for asking people directly about their lives and hearing their voices (and not for example the voice of their employer who reports their job information to the unemployment insurance system). Resume data may not capture everyone; these samples aren’t random. Lots of people don’t have a resume and not everyone has posted theirs online. This means the people in these datasets could be different in ways we can’t predict than those not in the data – which is the whole reason to go to the effort of obtaining a random sample.

People are generally also selective about what goes on their resume when describing their work history. If you look at mine, you won’t find my paper route, my stint at grocery store, or my years working at Old Navy. In the analysis that follows, we start with jobs held after age 21. For me that would include the Old Navy job, but not my other first jobs. We do this because 21 is a fair marker of adulthood in our society and careers are something we associate with becoming an adult.

First Look: How Many Careers Do Workers’ Have?

Why do we care how many careers workers’ have? Sociologists care about stability because it is hard to make investments in relationships and organizations which are the fabric of social life without stability. Instability in income, family life, schools, and neighborhoods – to name just a few arenas – have been found to have disruptive effects on people’s health, well-being, and economic mobility.

A pressing question for the future of work is whether workers are experiencing more instability. The analysis that follows is a baseline against which we can compare future cohorts of workers to identify the amount of change work instability, who is experiencing this instability, and where it is coming from.

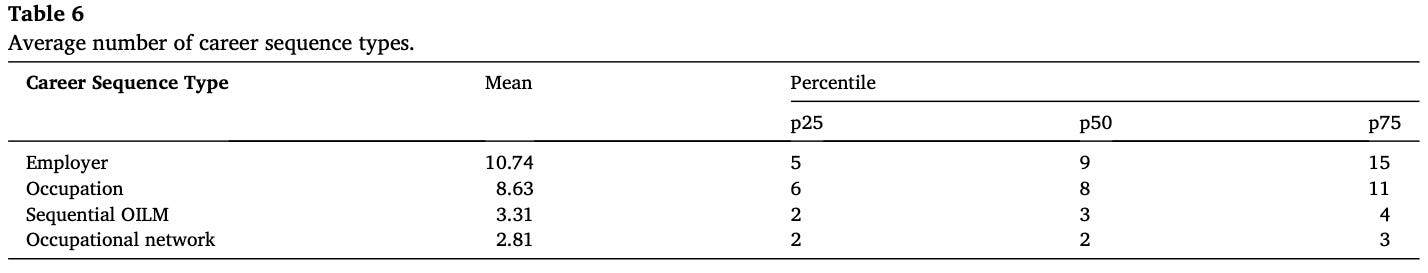

In Figure 2 and the corresponding Table 6 from my published article, we start by looking back at the number of firms or employers, and occupations held by people in the NLSY79 longitudinal survey over their work lives. As a reminder, the analysis is of the work lives of people aged 55 to 62 in 2019. On average, people in this cohort had 10.7 employers and 8.6 occupations over their work lives (see Table 6).

The medians (50 percentile or the number of employers/occupations the person in the middle of the line has if you lined everyone up from fewest to most) are close the means at 9 employers and 8 occupations. This means that the distributions aren’t too skewed “with a long tail” as the saying goes. You can see this in Figure 2 which shows the distribution (red line is firms/employers and blue line is occupations). If you picture the hump to be the back of a cat you can see where the image of the tail stretching out to the right on the figure comes from. Yes, there is some small proportion of people with lots of employer and occupation changes, but this is not many people.

Employer and occupation changes are common ways previous researchers have measured careers. What we do in our article is introduce two new approaches, which we call Sequential OILMs and Occupational Networks, that make sense of cross-occupational moves (described in more detail below).

Figure 2 shows that on average workers in the NLSY79 cohort have on average 3.3 careers measured using the Sequential OILM approach and 2.8 careers using the Occupational Network approach. That is a lot more stability than implied by the employer and occupation change measures of careers.

The take-away is that workers in this cohort, and remember they experienced the turbulent economic cycle of the 1980s early in their careers, had relatively stable work lives. This is the opening descriptive claim of our article. I will unpack more findings from the study in later posts.

What are the Sequential OILMs and Occupational Network Career Measures?

OILMs is an acronym for occupational internal labor markets and it is the idea that some occupations are not discrete, but linked together such that workers can move from one occupation to another occupation and remain in the same line of work or career. Labor markets are how workers are matched to employers. The argument of the OILMs concept is that the whole labor market is not one big pile of workers (or a pile differentiated by educational credentials and skills), but that workers enter many different occupational internal labor markets that may overlap and compete for similar workers.

These career measures build on the employer and occupation approaches by adding decision rules. So, a worker stays in the same career if they remain with the same employer or remain in the same occupation. The sequential OILM approaches looks at transitions were workers change employers and occupations and asks whether those transitions are career continuous or a career change. To make that call, we primarily use a measure of occupational similarity between each of the 500 pairs of occupations in the occupational classification system (see the full decision rules in Table 3 in the published article.)

The occupational network approach is similar to the sequential OILM approach in that it asks whether employer and occupations transitions are linked together. The main difference is the occupational network approach throws out temporality. Where the sequential OILM uses temporal ordering and asks whether the next job is linked to the current, the occupational network looks back over a person’s whole work history and group similar work sequences together into the same career using a network algorithm. The results are similar, so we won’t make too much of the pros and cons of these two approaches here today.