The Relationship of Low-Wage Work and Poverty

The challenge of individuals and households when studying economic mobility

This post is based on my paper included in Equitable Growth’s working paper series. I am highlighting a key chart from the paper that I also included in the accompanying EG blog post.

Rolling Downhill is a blog about economic mobility. If you’ve been following along these first two weeks, then you have likely recognized that the posts to-date have been about work and careers. Even more so, I have been focusing on sociological approaches to studying the careers of all workers. In contrast, economic mobility – while a seemingly neutral term about increases in economic resources – has a strong valence of mobility from the lower rungs of the economic hierarchy.

We typically don’t concern ourselves, as a matter of public policy, with economic stagnation or downward mobility of the upper classes. If a successful hedge fund manager or construction contractor’s daughter only becomes a small-town lawyer or a big 5 corporate accountant (or marries one), this downward mobility is not what we have in mind when we speak of economic mobility. The same goes for the electrician whose son inherits the family business; because of course occupations are inheritable for many reasons from familiarity, to informal apprenticeship, to genetic proclivity.

These examples point to two issues that underlie the concept of economic mobility: (1) what to do about households and partnership/marriage and (2) is the reference category the person’s parents (again complicated by household dynamics and gender) or the person’s work history. For example, is upward mobility starting at an entry-level job (however “high” that entry-level job is; engineers typically start high – relative to other jobs – in terms of pay for example) or starting in a low-wage job and moving up to better wages?. We won’t solve these issues today. Yet, as with most questions in statistics, social science, and public policy, most of the work is done in how the question is framed.

Low-Wage Work and Poverty: Individuals in the Labor Market and Household Economic Resources

For almost all people in the U.S., the majority of their income comes from labor or work. This is even true for most of the top 5% (go see the charts in Piketty’s Capital in chapter 8, which if you like this blog you might have on your bookshelf). Therefore, by definition, when we are talking about economic inequality and economic mobility in a post-industrial, capitalist economy, we are talking about the labor market. The labor market is the process of matching workers to employers. Employers pay workers for their labor to produce the company’s products or services and, if successful, remain in business and ideally make a profit.

Yet, humans have the proclivity to form households and this complicates things. Sociologists talk narrowly about households in economic contexts and not families because the concept of a family evokes a whole host of moral and ethical norms, social roles, and behaviors. I’m not here to engage in those debates today, so we’ll stick with households.

Households share resources, divide labor (within and outside the household), and often act strategically by setting goals and making long-term investments. In other words, they act like any other organization. Economists will point out that households are “efficient,” by which they mean pooling economic resources and dividing tasks does typically make it easier to pay rent or mortgage, food, and other basic needs – including social support. Yet, of course, if there is a high-level of relational strain or disfunction, then these efficiencies go away quickly – to use economic language again, they are a “tax” on the household. Sociologists generally believe people when they say they are better off not partnered or married; people don’t like to pay taxes.

When we talk about poverty, we are using a household concept: how well can this unit meet their basic needs? In the analysis I am going to show you, I use what is called a “relative” measure of poverty. This means that “meeting basic needs” is relative to the economic structure of the country. We might better call this relative measure a measure of economic inclusion. The measure I am using is uses a threshold of 50 percent of the median household income adjusted for household size. This measure is commonly used in cross-national studies of poverty across the wealthy capitalist democracies in Europe. Basically, this threshold means that if a household has less than half as much income per person as a “typical” household, then that household is in poverty.

Median household income have risen over the last 50 years and the threshold has moved up accordingly. The threshold in 2015 (last year of the analysis) was $39,113 in 2021 dollars for one person. The threshold scales with the square root of household size, which reflects economic efficiencies in adding household members. Two people is 1.41 times the threshold (square root of 2) or $55,149, three people is 1.73 times the threshold or $67,665, and four people is 2 times the threshold at $78,226. Importantly, I am estimating after-tax and transfer household income which includes two of the U.S. largest social safety net programs delivered through the tax code: the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC). Since households with children are larger, they are more at risk of poverty and so these transfers have large anti-poverty effects.

I am also defining low-wage work using a relative threshold: low-wage workers are those earning less than 2/3rds of the median hourly wage. This is about $14 an hour in 2021 dollars in 2015. Wages at the bottom came up in the late 2010s due to the tightening of the labor market and so the threshold if recalculated today would be higher even adjusting for inflation.

Aren’t all Low-Wage Workers in Poverty?

If you listen to the discourse, as I did before I ran these numbers some years ago, you might think that the problem of poverty in the U.S. is a problem of low-wage work or the “working poor”. Yet, only about 20 percent of individuals working for low-wages are in poverty. There about 150 million people aged 25 to 64 in the U.S. and about 5 percent are in low-wages and in poverty. This is about 7.5 million people; about the size of Dallas-Fort Worth or the San Francisco Bay Area metropolitan areas. So, a sizable amount. Yet that leaves 80 percent of low-wage workers not in poverty. The two concepts of economic inequality at the bottom are only loosely related.

Only 20 Percent of Individuals Working for Low-Wages are in Poverty

Unfortunately, the problem of poverty in the U.S. is more serious: it is primarily a problem of unemployment and underemployment. Since we are measuring income annually, if people don’t work enough hours in the year, they will experience poverty.

As William Julius Wilson titled his book on (racialized) urban poverty, the truly disadvantaged are those without jobs and without prospects for jobs. There are supply and demand side issues in terms of the jobs available (demand) and the skills and health of workers (supply). Studies of the long-term unemployed find there are commonly health issues, particularly mental health, at play that make it difficult for workers to participate in the labor market.

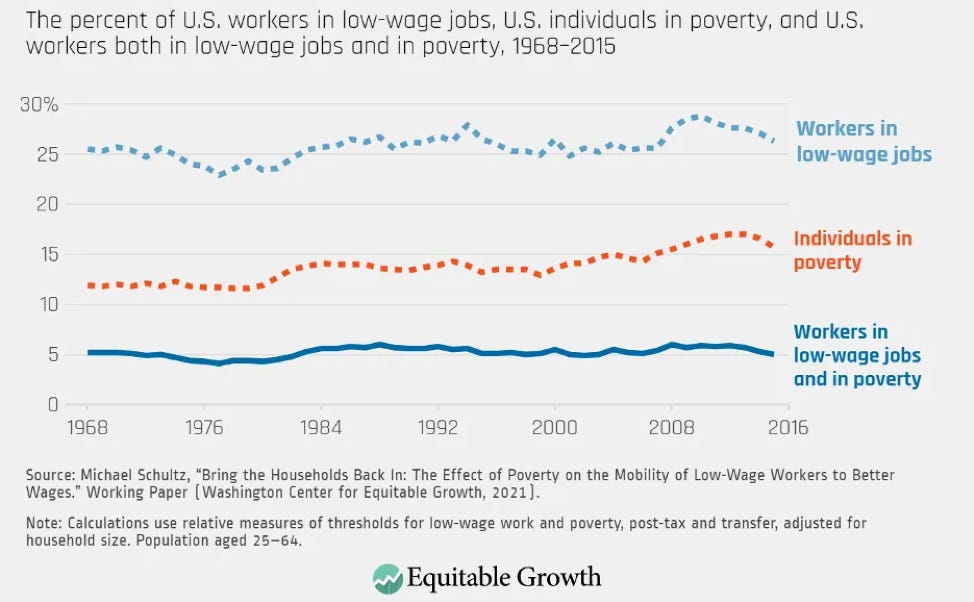

In Figure 1, I present the trends in the share of low-wage workers, individuals in poverty, and the overlap: workers in low-wages and in poverty. The universe here is people of working age, 25 to 64. Children and young adults under age 25, who are in households in poverty are not included in these counts. Households with children and those post-working age are at greater risk of poverty and so the share of people of all ages in poverty would be higher if all ages were included.

A final note on interpreting this figure. There is significant mobility out of low-wage work and out of poverty. Most workers and households only earn/have income below these thresholds for a few years. I will delve into mobility and these transitions in a different post. The point is don’t make the mistake of assuming that it is all the same people in every year of the data.

What should be striking in the time trend is the amount of stability. The share of low-wage workers has hovered around 25% of the workforce moving with the economic cycle. There is more movement of working age individuals in poverty. The 1980s economic turbulence and deindustrialization led to a tick-up in poverty. This came down some in the economic resurgence of the 1990s, but then ticked up with the early 2000s recession, before taking a leap with the Great Recession. The stability to me indicates that if I updated these figures through the present we would see more stability. Yes, there would be drops in poverty related to the temporary, pandemic-era transfer programs.

The risk of working age poverty looks to be strongly associated with economic downturns and dislocations. The precariousness of the modern labor market in then that economic instability may be greater and last longer and that economic restructuring results makes jobs and skills obsolete. The case in point is manufacturing workers in the Midwest rust belt who were dislocated when manufacturing moved South and out of the country. That these were high-paying union jobs only makes the situation worse. All the more reason for students to invest in general skills (like a BA and many advanced degrees), rather than in specific skills that may become obsolete more quickly.

The loose overlap between low-wage work and poverty means that there we need different sets of public policy. There will of course be spillover effects given the overlap, but my argument in low-wage work in an inherently different problem than poverty. Continued expansions of transfers to households with children like the EITC and CTC, will go a long way to addressing household poverty.

Low-wage work is more complicated. Given that about a quarter of low-wage workers work for less than the minimum wage (see Bernhardt et al 2009), raising the minimum wage runs into severe enforcement issues. I think the way forward it to better understand the processes and job ladders in the labor market that lead to job and wage mobility for low-wage workers. Consequently, I have focused my research agenda on understanding workers careers to better understand how to create economic mobility for workers at the bottom of the economic hierarchy.

One final thought: I presented this research a few years ago to economists at the University of Michigan who help run the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), the longitudinal dataset used in the analysis (a recording of the talk is here). The PSID was started in 1968 as part of Johnson’s “War on Poverty” to study economic mobility; the notion of course was to reduce poverty you need to understand it longitudinally.

In the Q&A, I remember someone pointing me to papers from decades ago about how raising the minimum wage won’t decrease poverty in the U.S. citing the same phenomenon I focus on here: the loose relationship between low-wage work and poverty. I wasn’t previously aware of those papers. It is a reminder that we sometimes may need to relearn what we already knew.