Vocational Training, Certificates, and Low-Wage Workers’ Mobility

Training-Job Matches and Specific vs General Skills

This is post is based on research I presented at the 2024 Research Evaluation and Self-Sufficiency Conference (RECS). See my RECS poster.

Education is the driver of economic mobility – or, so goes a common mantra. This is the case for the now much derided “College for All” movement in the 1990s. Some people seem not to remember that “College for All” meant community college. If you read between the lines of Rosenbaum’s 2001 classic book Beyond College for All: Career Paths for the Forgotten Half, he seems most dismayed at the way the College for All reform movement changed the way high school’s operate and shifted the locus of the vocational training system from the high school (the focus of his study) to the community college or other trade and education organizations.

It took me awhile when I joined this field of research to realize that College for All meant community college. This is probably because I grew up in a family where college meant: 4-year residential college experience as a coming of age experience between the end of high school and adulthood. Not so different from my grandfathers’ experiences serving in the military in the post WW2 Korean War Era of the 1950s (ironically the both served in Alaska). They both went to 4-year residential college on the original GI Bill.

Call me old fashioned, but I think if we neglect the coming of age (or to use a fancy sociological term, “socialization”) aspects of higher education and the military than we are missing a major part of what these institutions do. It is old news that we live in a time of declining cross-cutting institutions and the amount of trust in the institutions we do have is in decline. I am talking here about the decline of religious organizations, unions, and volunteer clubs and organizations. As Chris Hayes’ writes in his 2012 book Twilight of the Elites, major scandals have rocked Wall Street, Major League Baseball, the Catholic Church (and many other children-serving organizations like the Boy Scouts of America), and the government. Two of the primary institutions left standing are the colleges/universities and the military – and these certainly have piled up their share of grievances in my lifetime.

All of this is to say is that we misjudge the education system if we think its main purpose is to develop skills. From an economics perspective, maybe everything can be reduced to skill. So instead of socialization, we talk about individual “soft skills” or (in the new lingo) “durable skills”. When we make the shift to skills, I think we lose something that is important. What people experience collectively shapes how we relate to one another and what we are building together through our shared institutions. Part of what is at stake is a vision of the type of society we are bringing about. Is education and training an individual project or a collective one?

One of many reasons I will encourage (and pay) for my children to attend a 4-year residential college is because my experience as an undergrad was central to my own development of self and the solidification of a set of values that I hope (no guarantees!) my children will inspect and choose for themselves. I don’t think higher education is the only institution that facilitates that. As I write this in Spring 2025, the Trump Administration has disbanded and sent home AmeriCorps community members serving across the country. In my view, we should be providing more support for young adults to take on these kind of experiences that facilitate pro-social orientations that serve workers well in the social organizations that are workplaces.

The purpose of this preamble before I share my research on vocational training and low-wage workers’ mobility is to orientate us to the broader question of what we want out of the vocational training system. Part of what I hear in the discourse is that what we want is a set of social experiences that are different from 4-year residential college, but similarly provide meaningful experiences (and skill development) that lead to stable careers. The research I am going to share doesn’t directly test or contradict this larger vision.

The next section is an overview of the theoretical discussion of general vs specific skills and how vocational training fits in. It sets up the key variable in my analysis which is the match between a worker’s vocational training and their job. If you want to get to the results, skip to the last section.

General vs Specific Skill Education Systems

The U.S. education system is widely recognized in cross-national comparative perspective as having a general education system. The U.S. system is organized around two credentials: high school diplomas and 4-year BA degrees. Given the continued rapid growth of advanced degrees, these are an important part of the system. However, my focus today is on economic mobility from the bottom of the economic structure, so I am going to set aside advanced degrees for the time being.

Both high school diplomas and 4-year BAs operate as general credentials in the sense that they for the most part do not prepare people for any specific career. Yes, higher education institutions have responded to increased demand for pre-professional majors and tracks, but this doesn’t change the fact that the system itself (and the meaning of a BA overall) is a general system. A general education system focuses on the “basics”: reading, writing, math, science, arts and a broad orientation towards problem solving, teamwork, and learning how to learn.

The rationale of general education system is that it isn’t useful to teach students too many specific skills. If students change their mind and go into a different field, those specific skills may be irrelevant. Furthermore, education curriculum typically lags what is happening in industry. What might be taught in a classroom may be out-of-date, or lack the context needed to make it relevant at a particular employer. Finally, investment in specific skills is risky in the face of technological change and global markets. Workers may be left out to dry if the skills they invested in become obsolete or the industry moves away. The case-in-point being the decline of manufacturing in the Midwest and Northeast of the U.S. I have heard that the construction trades have had difficulty recruiting young workers. I don’t have any evidence, but I have wondered whether the collapse of the housing crisis that coincided with the Great Recession had a lasting effect on the perception of having a stable career in these jobs.

A general skills education system encourages exploration, keeps more career pathway options open for longer, and ultimately increases upward mobility (all else being equal; which it is not between countries) by making it easier to change jobs and tracks. Students in education systems with a more specific skills emphasis typically track students earlier and have more credentialed labor markets such that it is harder to obtain jobs without having completed the required educational programs.

The flipside is also true: the most successful specific skill training programs channel students to specific jobs at specific employers who are heavily involved and invested in these programs. This is where apprenticeship and related programs come in. Although my read of the research is that it isn’t so much the “intern” or “temp” like employment contract aspect of apprenticeship that matters as much as the employer involvement. Employers can commit to strong linkages with school-based training programs and on-the-job training without a traditional apprenticeship employment contract model.

In a general skills education system like the U.S., there is expected to be wide range of student outcomes. Yes, there is a college earnings premium on average, but beware of the average! There is widespread inequality in earnings and career outcomes for college graduates along all the typical divisions of inequality in this country: geography (which corresponds to labor market dynamism and economic development), the prestige/selectivity of the institution, family background, race, gender, etc. All of that is to say that the education system is only one part of the system of that creates and recreates the economic structure and facilitates economic mobility. We should reject simple narratives. The labor market is complex and the linkages from the education system are not always straightforward.

Part of the intention of a specific skills education system is the reduce the variation in outcomes for workers with specific credentials. Credentialing and other formalization practices are intended to reduce the role of other “non-credential” factors in the hiring process. In the U.S., we are probably most familiar with these practices in unionized, government bureaucracies that turn to formalization as means of “fairness”. Now certainly it is a type of fairness defined relative to the formal rules, but proponents would argue at least there is a set of rules. Research on licensing requirements for occupations by Redbird finds that licensure increases access to newly licensed occupations for marginalized workers. A similar argument is made for the use of standardized test scores like the SAT and ACT in college admissions. Yes, the standardized tests have flaws, but at least it is a formal system with some claim to an objective standard; subjective standards have been typically found to result in greater exclusion for people from marginalized groups.

A specific skills education system is supposed to channel students to particular jobs where they use their specific skills. As a result, if we want to evaluate a specific skills system, we need to evaluate the match between a worker’s training and their job. Indeed, the theory of a specific skills system would lead us to think that there is limited value in specific training if there is not a job match. In contrast, matches between training and jobs are less relevant in a general skills system as employers do not expect workers to have specific skills and are not for the most part evaluating potential hires on specific skills.

Job-Training Matches and Mobility Out of Low-Wage Work

In my previous posts on my research papers, I have been slowly moving through from front to back highlighting and contextualizing key descriptive results. I’ll eventually get to the regression models at the back of the papers. Today, I’m going to cut right to the chase. There is more to unpack here, but the top-line stands well alone.

The data I am using comes from the national-representative longitudinal survey, the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) from 1984 to 2015. This is the same data I described last week when asking reporting on mobility rates out of low-wage work. The analysis focuses on workers observed entering low-wage employment spell who are age 25 to 54. The basics of the model and analysis of mobility are the same. The difference here is I am zooming in on the role of vocational training and training-job matches on mobility out of low-wage work.

The PSID asks the respondent whether they received a certificate, license, or vocational degree as part of the education module. They further asked for the field of study with 20 broad categories as the available answer choices (e.g. Health Related, Computer Programming, Skilled Crafts). I determined training-job matches by matching these broad training codes to detailed occupations. It is important to keep in mind this is a coarse match. The broad nature of the field of study for the training likely means more people are being identified as having a job-training match than a more refined measure of field of study.

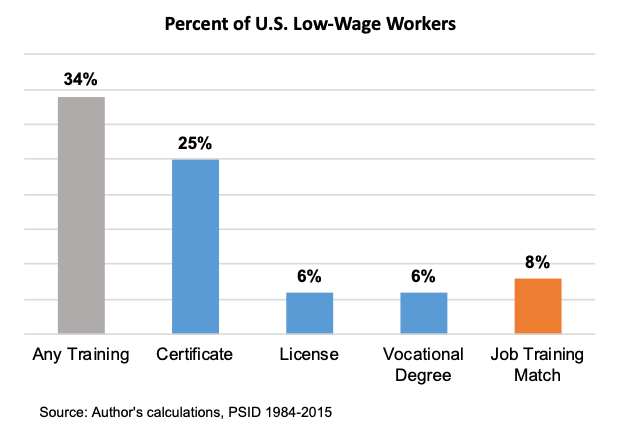

About a third of low-wage workers report having vocational training. Certificates are the most common type of vocational training. About 25% of low-wage workers in the sample have a certificate, followed by 6% reporting a license, and another 6% reporting a vocational degree.

For U.S. low-wage workers with any vocational training, the training-job match rate is 26%. This seems low to me, especially given the broad nature of the field of study categories to determine the match.

For some perspective, I conducted a parallel analysis for West Germany using the longitudinal German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP). The GSOEP includes a direct question where the respondent is asked whether their vocational training matches their job. So, not an apples to apples comparison with the U.S. PSID question and a very different context in a vocationally oriented, specific skills education system where the match rate would be expected to be higher. I find that the job-training match rate for low-wage workers is 47% in West Germany.

My research question is whether vocational training and job-training matches in particular facilitate upward mobility. Now a first attempt would include the “any vocational training” measure in the model predicting low-wage workers mobility. In a preliminary model, I find that any vocational training has a positive, statistically significant effect on low-wage workers’ mobility. In other datasets, this is about as far as you can get if the data do not allow for differentiating the types of vocational training or the job-training match.

It would be a misunderstanding of the model to stop with this measure and conclude all vocational training has a positive effect on mobility. What this first model is saying is that on average the effect of vocational training on mobility is positive. If there are large differences in the effect of vocational training given the type or other conditions (like the match) than this baseline positive effect could be misleading. This is indeed what further analysis finds and it is a reminder to that consider the limitations of the data when interrupting analysis results.

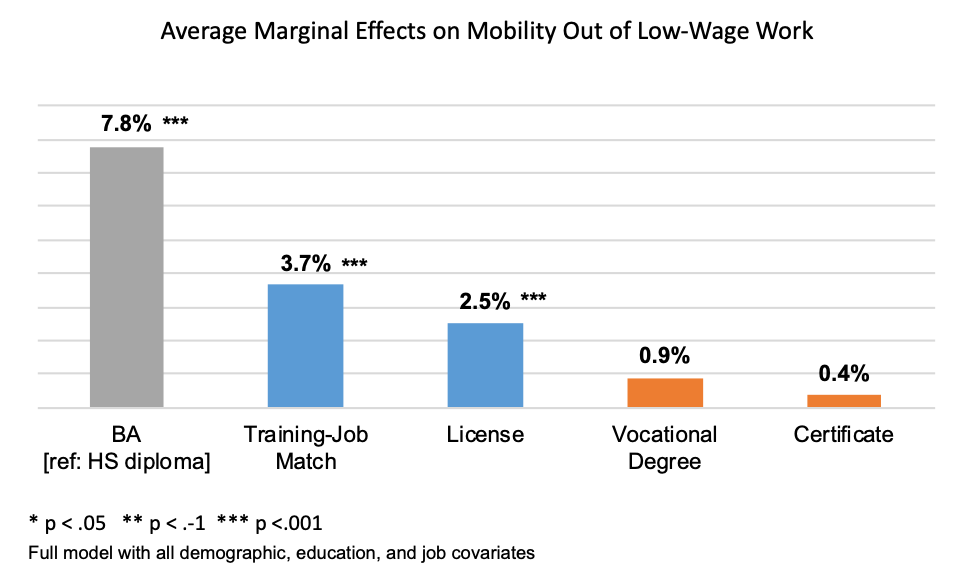

I find that the effect of vocational training primarily operates through the job-training match. This is consistent with the idea that vocational training produces specific skills and not general skills. The effect of a job-training match is about half the size of the effect for a worker having a 4-year BA+ credential over a college degree. The way to think about these effects is as changing the shape of the curve of cumulative upward mobility since entering low-wages. The Average Marginal Effect seeks to capture in one number the way the curve is changing.

The effect of vocational training operates through the match for certificates and vocational degrees, but not for licenses. In other words, workers with certificates and vocational degrees that do not match their jobs are no more likely to be upwardly mobile than those without these vocational credentials. Licensure looks to operate differently as I find a positive effect for licensure on mobility even when the field of the license does not match the job. This may indicate that licensure can act as a more general education credential or that licensure leads to upward job pathways that the coarse job-training match isn’t picking up.

There is growing interest in non-degree vocational credentials. My research indicates we need to be paying attention to training-job matches as a central aspect of evaluating the value of these programs. The good news is that initial job placement data may be easier to obtain from these programs than longitudinal earnings data and could be used to determine whether the rate at which the programs are producing training-job matches.